Chicago 2008

Chicago was different this year.

I started doing this race in 2005, when it was more of a question of whether or not I’d be able to complete it. That race morning featured the usual eight thousand people, but more troubling, I had tightness in my chest that I thought was nerves, but turned out to be the onset of some sort of bronchial infection. I couldn’t breathe very well at all and it took me just under four hours to finish.

In 2006, like everything else in my life, I survived the race. I cut about twenty minutes off my time from the previous year, and I was glad to show improvement, but it was almost time to take things to the next level. I got a new bicycle and was recently divorced; I wanted to get better at the sport. I bought a computerized trainer and doubled up my personal training sessions. I was going to be a triathlete, not just sort of do it for a couple of weekends out of the year.

I set up an absolutely grueling season, starting in March with the Lake Havasu Triathlon, adding the Rage Triathlon in April, Tempe in May, San Diego in June, Chicago in August, Lake Las Vegas the Saturday afterward, Las Vegas at the end of September, and Pumpkinman in October. I did all of those races except Rage (swim cancelled due to wind and overall terrible weather) but my Chicago time was the best all year. I did it in 3:02:29.

And I spent a year agonizing over those two minutes and change. Even though I’d run the best race of my life. Even though I was thirty-five minutes faster than the year before. And even though I said at the post-race party, “Look, if you can’t be happy about doing the best time you’ve ever done, you’re in the wrong business” I spent a lot more time upset about it, pushing me towards one more crunch, one more mile, one more lap.

So I knew one thing leading up to Chicago this year; I was not going to be outworked for it.

Nannette had moved, so I hired a trainer that could help with endurance events. She showed me Pilates and for the first time in my life I had some level of core strength. I put in the full 18 weeks of training like I did when I did this race the first time, losing 42 pounds in the process and getting to my lowest weight since high school-203.

Rather than spending two weeks of the year lounging about France, this year I was out in Chicago with the kids in July, soaking up nice weather and working out with treadmills and weights every other morning. I ate good food but didn’t go crazy. I suspended my workout schedule but resumed it on my return. I did everything how I wanted to and I hoped it was going to pay off.

I’d shipped out gear to arrive while I was in Chicago, which made some of the training rides interesting when I realized that I’d shipped too much of my stuff. My tendency towards overpreparedness works nicely when all of my stuff is sitting at my truck in the hours before a race, but it doesn’t help so much when I’ve shipped both pairs of my racing sunglasses to Chicago when I have two training rides at Lake Mead. I think I did one of those rides in a borrowed pair of knockoff Chanel sunglasses cheerfully lent to me by my coworker, Lisa.

But anyway, I came into Chicago with a very clear mission of what I wanted to accomplish. Part of what bothered me a little bit was actually how focused I was. I mean, I’d spent a whole lot more than two minutes and twenty-nine seconds worrying about two minutes and twenty-nine seconds. There were several factors involved:

Prizes. I’d wanted to get a grown-up watch, one with hands, a blue face, and that looked like I could wound somebody if I were to backhand them on the side of the head. Something with gravitas. Heft. I’d liked Tag Heuer watches for a very, very long time. I liked the shade of blue on the face. I liked the design elements, which were subtle but which didn’t scream “look at me.” I liked it wasn’t as clichéd, or frankly as expensive, as a Rolex. And in 2007, I promised myself that I wouldn’t buy one unless I finished a race in less than three hours. The year came and went without a sub three hour finish. Getting as close as I did that year made me more determined to make sure that THIS was the race, THIS was the year, and I wanted to spend years walking around with a big ol’ trophy on my left wrist.

Pride. I had improved my times in the races earlier that year by nine minutes or more, and everything looked like it was on track for Chicago to be the race of a lifetime. And I wasn’t quiet about letting people know that this was what I was going for; this was meant to make sure that people would ask how my training was going whether I wanted to tell them about it or not. Whenever I felt tired, I thought of what it would be like to go back to all of those people and tell them that I hadn’t worked hard enough to reach my goal. That I didn’t feel like staying on a diet. That I was just too sore to push myself harder, but hey, thanks a bunch for getting up at the crack of dawn on Sunday morning to come check it out. Sorry you wasted three hours. In another way, so did I. I refused to let that happen.

Tequila. In the days leading up to the race, I promised people over E-mail that, if I were to break three hours, I’d be enjoying three shots of Herradura tequila at the Spectacular After Party at Lalo’s, described on its own website as “This bright tequila is magnificent from bottle to glass to palate. It carries its own light.” I said if I went under 2:45, there would be worms involved. (Yes, I do think the worms are kind of gross, but to beat my previous best time by almost 20 minutes would leave me so deliriously happy that I might not even notice.)

I had all this in mind when I hopped on a USAirways flight to Chicago on a Thursday morning. I had one gigantic full suitcase that had an eclectic mix of triathlon gear, workout stuff, business casual clothes, race equipment, and toiletries to accompany me. In my carry-on bag there were the items I wouldn’t be able to replace if they were lost: my bike shoes, my running shoes, my laptop, and my traveling books.

An uneventful, and surprisingly on-time, flight got me into Chicago’s O’Hare Airport and to the rental-car counter at a reasonable degree of speed. They put me in a small SUV, a Chevy Trailblazer, as requested. I was a little hurt that they didn’t have something visually unique. When given the choice I’m usually pretty skilled at selecting the absolute ugliest car in my category; that way I never have to worry about losing it in the parking lot. This vehicle was so normal-looking that it would certainly present more of a challenge. I had some time, so I picked up my bicycle over at Oak Park Cyclery, where the owners had done a marvelous job of putting all of my stuff back together, hanging on to my business cards from July’s reconnaissance mission to see if they were organized, fielding my phone calls providing them with the FedEx tracking numbers to prove that yes, the bike was on the way, verifying the status the day before I got there, and helpfully stapling all of it together for when I arrived.

I’d had a minor dilemma that illustrated what kind of training season it had been as I was going in to the race. My aerobars have pads for my elbows, and the sweat from my hands and elbows had worn out the glue. This caused the pads to fly off. I was hoping the bike shop had more; my bike store didn’t. They were out as well.

Then it was off to my parents’ for dinner, and Julie was nice enough to let me stay with her. She was even nice enough to let me keep my bicycle in the bedroom with me; I don’t care how many locks are on the utility closets, my ride stays in a room of its own at my house, does so in various hotel rooms during the year, and only occasionally spends the night locked in the truck. As I explained to Jon, who had the misfortune of riding in the back the year before and didn’t understand why the bicycle may have to take priority over his comfort and safety, “If you spent as much time in proximity to my testicles, I’d grant you the same level of respect.”

On Friday morning, I’d performed the impressive trick of setting my alarm on my cell phone to wake up at eight so that I could be ready to get in a run, without changing the time zone from Pacific to Central time, so I was running a short spot late but felt rested. The routine for Chicago is always the same; I fly in on the Thursday before the race, do a three-mile run on the Friday before so that I can get used to the humidity, hit the expo and body-marking on Friday afternoon, catch a nice dinner on Friday night, rest on Saturday, and hold the Last Supper dinner at a seafood restaurant on Saturday night. Sunday is race day, and we meet for dinner, usually at a Mexican restaurant that’s better than anything else I can get out here, even though I’m a thousand miles closer to Mexico.

Usually my run takes place at West Field at Lyons Township High School, where I went to high school. That was the track that I ran on when I won Physical Education Student Of The Month for a jogging unit, despite being overweight and not much of a runner, because I employed a principle that I wasn’t going to stop and walk. The proto-genesis of my own insanity can be traced to this one location, and I get reminded again why I love racing here. The weeds on the cinders were always in the same place. The fences were always the same. The whole experience felt like it was frozen in time and I get to be 15 years younger. The only thing that was different? The light. My gym class was always in the afternoon.

However, there was one thing that I realized this year: I didn’t live there anymore, and my parents didn’t live there anymore, and I didn’t have in-laws anymore so I didn’t stay there anymore, and a bunch of my friends don’t live there anymore, so I was going to drive for 40 minutes to run for 30 minutes, and that just didn’t make sense. I’m big on tradition but like to think I’m bigger on common sense. I did my running at the high school track that was three-quarters of a mile from my sister’s place.

The football team was practicing, the trains were going by, and there were plenty of people from the neighborhood walking around the track. On the next field over, the band was practicing. While I was used to absolute silence at West Field, this at least gave me something else to look at. Otherwise, it was the same set of MP3s as it would be in the gym back in Vegas, same shoes, same running surface, everything that I shoot for when I do this workout. The variable, though, is the humidity. Sometimes I come back and if it’s rained the night before, it’s like breathing soup; I’m used to training in the desert now, and going home is an environment with pluses and minuses. On the bright side, running when it’s 82 doesn’t bother me anymore. The problem is having to practice a day after it rains, which it never does.

I made my way back, showered, and got set for the greediest portion of my day. Ken, Jon, and Siobhan, who I hadn’t seen in a decade, were going to be tagging along for Expo Day and lunch. We all met up and drove downtown. The reason this was the greediest portion of my day? How often do you get a group of four people to do whatever you want? You can if you specify what the plan for the day is going to be and it’s going to revolve entirely around your schedule as a visitor from out of town.

I always learn something about my friends after I haven’t seen them in a while. This lesson was that the use of “war criminal” as an insult to a motorist who cuts you off may be a little over the top. We parked across from where we were going to have dinner that night.

Our next stop was yet another milepost on the nostalgia tour. I like to build in nice rewards for having a good year, and there’s no better place to reward myself than the Café at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. As we walked over, though, we saw a union protest, and as a proud alumni and EmPact severance recipient, I couldn’t resist the following:

We went up the Water Tower escalators, past the jumping globules of water, and I was concerned that since the movie theater towards the back was no more, would the secret mall elevator still be there? It was, but the touch-sensitive button had been replaced by one that actually needed to be pressed, so we waited an extra five minutes for an elevator that I’d never summoned.

I was at home in the mirrored and chandeliered elevator with parquet floor; for a long period of time this was quite literally another day at the office. But after a couple years away, when the doors opened and you could smell the fresh flowers, hear the rush of the water fountain, see the light shining across the bar at the Greenhouse, look at the side of the Hancock building, and feel like Somebody. Or, in my case, feel ten years younger, when I used to lunch here all the time.

We were promptly seated, in a booth directly across from the usual table for Mondays, when Mr. Lyden and Mr. Mascheri were called away from the urgent business of Commerce to recharge their batteries next to this fountain. The staff knew who we were and what we were drinking, they knew our names and what sort of schedule we were on. I watched us stroll past harried men in suits like they weren’t even there. I was young and doing well and the staff loved us. They even told me later on, when they saw I’d hired on as Assistant MIS Manager, “It’s going to be as wonderful to have you as a coworker as it was to have you as a guest.” I’m sure they thought so, but the experience had its ups and downs from my perspective.

So, hip deep in memories and my mind a million miles from the upcoming race, I sat back and ordered a passionfruit iced tea and some French onion soup, which wasn’t on the menu but which they could happily provide. Everyone else ordered burgers and sandwiches, and I spent most of my time baffled that I was in a conversation with Siobhan for the first time in nearly ten years.

After lunch, the fact that we were not going to be walking to the expo meant that we had some time to kill, so it was off to another favorite haunt, the Museum of Contemporary Art. I’ve always like the building itself, and the art’s usually pretty snarky and funny. Ken and I are museum veterans; we’ve got little epaulets that look like croissants after last year in Paris. Siobhan digs modern art. Jon…well, I was hoping we wouldn’t see anything horrendously offensive, even though Jeff Koons was the featured gallery artist.

We came in down by the koi pond and started making our way through the museum, stopping occasionally to snap some pictures of the windows, and pretty soon we were overlooking the central atrium. I stood there for a while, because I wasn’t just looking at a giant Mylar heart ornament. I was looking down at a whole different life.

Once upon a time I was a technical specialist in the far northern suburbs and my girlfriend worked at a realty and design firm over near where I used to go to school. We would commute together in the mornings and would spend a lot of nights downtown after work. We still lived at home, but did all kinds of stuff more characteristic of people like us who lived in the city, including museum fundraisers.

One of these was the RED party at MCA, held in December of 2006, where the invitation said, “Bring a friend. Wear red. Expect some sizzle.” I remember her body framed against my black suit and red, black and white squiggly tie. I remember the red dress. I remember the museum’s development director introducing herself to us. I remember…

“You OK?” Apparently Siobhan was concerned that I was aimlessly staring into space.

“Sure.”

We moved on to the gift shop, where I found the stuffed plush microbes on a table, then immediately made sure to juggle them and play catch, ensuring that my fellow travelers caught gonorrhea, syphilis, and salmonella.

After this, we took a few pictures outside. Jon had held up well, even through the room of the Koons exhibit that was nothing but billboard-sized hardcore porn. (And do not confuse this with simple nudity; that was the rest of the room.) We’d also seen a 15-foot tall aluminum balloon poodle. The one pictured outside is real and life-sized inside.

We walked for a block and picked up Julie’s entry for Nike’s Human Race, an attempt to stage a 10K race all over the globe on the same day. Chicago’s would feature swag, free shirts, free food, and a concert at the end of it. I would be able to pick up her timing chip two blocks away from where we were eating lunch instead of her going eight miles out of her way on Saturday, so we agreed that was a smart idea.

Following the Nike Town crush, we made our way down to the Expo, hopping in a cab and cruising down Michigan Avenue. We were soon at the Chicago Hilton and Towers, getting ready to sign up for my race.

Now the Chicago Triathlon is the World’s Largest Triathlon, and this would be my fourth time racing it. The procedure from year to year is the same. At most of my races, there’s a card table where I tell them my name, they hand me an envelope and a bag of free stuff, and I go on my way. I rarely check out the expositions any more; I have so many free samples of nutritional products that I could probably live off of them for a month, and I don’t buy new gear right before I do a race. I’d rather go to my local bike shop and give them my money than someone from out of town.

But the sheer amount of competitors makes this an attractive business prospect for any vendor. Xterra wetsuits sells more wetsuits at the expo than they will in a quarter online. So people who sponsor the race, or sell to triathletes, or even those who have nothing to do with triathlon at all want to have a place here.

The expo is held through three conference rooms in the basement of the Chicago Hilton and Towers. I was attempting to explain the race to a coworker who does triathlons, so I took as many pictures as possible. We made our way downstairs, where a bank of laptops awaited. We would sign in with our information to receive our race number, which would be the key to everything else at the rest of the expo. My number was 8316. I moved with grim familiarity towards the next room, waiting to see what the crowds were like.

Jon had joined Ken and I for the Expo last year, but this was Siobhan’s first exposure to the triathlon community and some of our more arcane rituals. We stepped into another room and I signed a swim waiver-a legal document in which I acknowledge that yes, I can actually swim that far, yes, I understand this could kill me, yes, I’m willing to do it anyway. When it came to packet pick-up we were several steps beyond a card table. What awaited us was a gargantuan row of a dozen volunteers, manning a long row of cardboard boxes. I picked up my envelope after showing them my USAT card and went to check in my chip.

The race will give you a plastic band to attach your chip to and they will cut it off at the end of the race. Two years ago this sliced into the back of my leg, leaving a very nice inch-long scar on my right ankle. I have since purchased my own Neoprene and Velcro chip strap and my own chip, which I registered with race officials, justifying carrying it around in my pocket all day. They do this by verifying that the six-digit number I sent them matches, then running it across a scanner and making sure it’s my name and number that pops up on the screen.

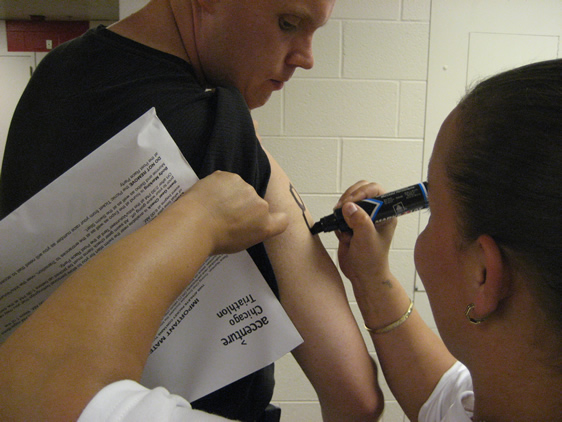

Then it was off to body marking, even though the race wouldn’t be for two more days, but without proper sanding, a permanent marker won’t come out. They write my race number on both of my arms and my wave number on my legs. The numbers on my arms are to be seen by the officials and photographers if, for some reason, they can’t see the number that’s stuck to my helmet. The numbers on my legs are so that I can tell by looking at the rider in front of me how I am doing in comparison to the rest of the race. If the numbers are mostly smaller than mine, those racers started earlier, and I’m doing pretty well. If they’re bigger, I probably have some work to do.

Once body marking was complete, it was time to make our way through the first part of the expo. I have no idea how they decide on the order of these things as a layout, but every year it’s the same merchants in the same place. The good new about this particular arrangement is I know where everything is that I’m looking for, every single year. This is where I buy socks and supplies that would be harder to find anywhere else, such as my aerobar pads. In addition, there’s usually all sorts of food to try, which my traveling companions appreciate, even though I can’t eat any of it until after the race. The year before Jon went through about three bags of jelly beans before realizing that they were to be consumed as part of a training program, complete with instructions on the side for a precise energy-restoring carbohydrate and electrolyte balance, as opposed to just eating a bunch of Gatorade-flavored jellybeans. Years of research has yet to convince me that Jon’s approach isn’t the correct one.

We made our way through an entire section of energy bars, gels, fluids, and other substances that no self-delusional triathlete can do without. (James’ latest pot-kettle-black remark has been brought to you by Gu Energy, Nuun Active Hydration, and EAS.) I advised the others that, while I could not eat this stuff, they were welcome to try as much as they wished, and I would try to recall for them which ones tasted like dirt mixed with nutmeg, raw sugar stirred in glue, and some which might be, on a good day, akin to an actual food product, something that a normal non-racing human being would want to consume in real life.

The problem with these items is that they’re designed for situations where you’re actually racing, not as ordinary snacks. I’ve seen full size nutrition bars that have 450 calories in them. Would you want your daily diet to consist of five nutrition bars? Of course not. But when I’m racing, I burn about 2200 calories and lose between six and eight pounds. On a hot day, if I don’t put something back, I’m a few steps from hallucinating.

Besides, as I’m running, I’m breathing through my mouth and nose and drinking lots of water, so texture is more important than taste. The taste you want to disappear. But I don’t want anything stuck in my teeth if I have to eat it while I’m riding or running. That just gives me one more thing to think about.

The good news is, in Olympic races like the one I was doing, nutrition is a factor, but you can screw it up and you’ll live. You’ll feel pretty lousy on the run, but you’ll get through it. You do not have the same luxury in a race like the one I would be doing in the late fall, the Silverman half distance. The calorie burn for that race will be off the scale. (I found out after I ran it- 4,336 calories, or 2.5 days worth.)

But what I couldn’t do is eat sample bars like they were hors d’ouevres; with the number that were in front of me I’d eat two days worth of food in twenty minutes, then wonder why my legs were moving like glue on Sunday. As a result, it’s a standing rule that I don’t eat or drink anything at the expo, but I’m happy to pick up wrapped samples to try after the race.

I walked to the back and picked up my race shirt, making sure that the sponsor on the back was somebody whose product I might actually use. One year I was wearing a shirt that had some kind of lung training medication on the back, and people started asking me about it at the gym like I knew what I was talking about. Then again, my race shirts go into a curio cabinet that was an interesting time and place summary when I started out but which now is a very large pile of laundry, and I know that this one will be folded down until all that’s left is the logo of the race, maybe the date.

We walked around some more and found several items of interest. Siobhan liked the idea of a summer camp group visiting the expo for great ideas on how to get healthy-and every one of them queued up at a wheel of fortune, trying to win free food from McDonalds. I put everyone on a mission to find me stickers for the platform of my CompuTrainer, making it so that I could look down and see things when I didn’t feel like looking out of my office window. Because of Las Vegas’ heat and traffic, about 90 percent of my summertime bike riding takes place indoors. Pick any window in your house and stand in front of it for two hours. You can see where I’m on board with virtually any type of visual distraction.

As we were walking near the Crocs exhibit, where they were giving away an entry and trip to Las Vegas for the Marathon, we saw an older couple, the gentleman in a track suit and wearing a visor, the woman in a track suit with pink spiked hair. They looked to be in about their 70s. Siobhan, Jon and Ken were motioning with their eyebrows, and I nodded slowly, but I pointed out something else.

“That gentleman’s visor marks him as an Ironman Florida finisher. We are not worthy to share oxygen with him. The woman with him can wear whatever she likes. Avert your eyes, mere mortals, for we are in the presence of excellence.”

I wanted to catch the course talk, because I’d heard horror stories about what the roads were like, as apparently they hadn’t been maintained following the winter, and there were a large number of potholes. What’s annoying and damaging to a vehicle could be injurious or fatal to me if it happens in the wrong place at the wrong speed. They were in the midst of explaining the run course, and everything about it, right down to the overhead projector, the room, and the man who had given the speech, hadn’t changed from a year ago. I stood on the perimeter of the meeting and watched the usual questions get asked.

A woman started asking me a few questions that went from the mundane – “When’s the next meeting?” to the uninformed – “How many laps do the sprinters do on the bike?” – to the terrifying – “What’s a transition area?” I had an awful vision of this poor woman cruising along on a bicycle in front of me, wicker basket on the handlebars and helmet on backwards, while I’m screaming down the street and she’s wondering which exit to take. She may even have a left blinker on despite the fact the bike doesn’t have turn signals. She was much shorter than I was, and I faced her directly, bowing down to her to whisper while the meeting was still taking place.

“Have you ever done a triathlon before?”

“No.”

“Have you ever done these distances before?”

“No.”

“OK, you’re going to want to do this. Ignore the rest of this meeting, because you’re going to want to see the whole thing. There’s a guide and paperwork and maps in your bag. Read them. There’s a wetsuit rental place right over there-get yourself one, the water’s going to be in the 60s and it’s a shock if you’re not used to it. Catch the next meeting. Listen to all of the questions. Good luck and have a great race. She wandered off in the direction of the wetsuit rental place, and I dove in to ask questions that I had shown up too late to hear answered.

“How’s Lake Shore Drive up north?” I asked the gentleman who gave the speech.

“Bad. I drove the north part of it last night after dark, and some of the concrete’s a mess.”

“Now there’s two inside lanes blocked off. Is the second lane a travel lane or just a passing lane?”

“You can use it for passing, and the inside of it is probably legit for travel, but the far left is if you get passed. The rules apply out there.”

He’d given me all I needed to know; a better ability to seed myself against the other cyclists. I knew with the amount of bicycling I was doing, I was going to be a faster rider than most of the entrants. The problem with this is there’s not a lot of safe ways to pass when it’s three wide in the left center lane of Lake Shore Drive, and if that second lane was exclusively for emergency vehicles, I shouldn’t be in it. But after finding out that I could use it as long as I was passing people, this changed my whole outlook for race day. The year before, I’d gotten cut off by someone and didn’t have time to correct before hitting a pothole the size of a volleyball. I risked a penalty for language for saying something particularly nasty to the person who passed me, then I had to coast for a bit and make sure that I still had an attached wheel, a full tire, functioning brakes and the like. Remember that I finished two minutes and change off last year’s goal and this was one of those little moments that stuck with me.

Ken and Siobhan got their cell phones set up to receive race updates at a set of laptops. The Chicago Triathlon is unique in that it will send updates from the timing mats out via text message. I’d sent instructions to everyone on how to do it so they could follow the race along with me. They’d receive little bulletins like “JAMES LYDEN finished the SWIM portion in 33:00” as I was moving along.

After the meeting, we made our way out to get dinner. Once again, the call is mine; and my choice was Heaven on Seven on Rush, for a number of reasons. First off, the food is always excellent, and I can’t get good Cajun food out here since they closed Commander’s Palace. Second, I can’t eat anything that’s on the menu, but the stuff that I can eat is generally nutritionally sound. I can get a cup of the gumbo and know that the next day’s nutrition plan will cover anything that’s a little excessive.

We were all grateful to get off of our feet for a little bit. Siobhan had no idea what to order, so she delegated her entire meal choice to me, and I asked her a couple questions about what she thought about seafood in general. She mentioned something about texture, and that’s how she got tilapia with a lobster stuffing. I had the Shrimp Angry myself, moving towards the ever-popular all seafood diet a day early. Siobhan also had no idea what to drink, so I advised a hurricane. For the uninitiated, that’s a whole hell of a lot of rum and enough fruit juice to make you say, “Hey, there’s a lot of booze hiding in there, huh?” Giving this to someone who said that she acted like Jim Morrison on two glasses of wine could be construed as criminal mischief in some states, but I figured if I couldn’t drink, someone else would need to act as my surrogate, and I figured I could always shoot for entertainment. I considered ordering an Abita or Dixie Blackened Voodoo, but quickly changed to a club soda. I don’t drink three weeks before races, and try to knock back as much water as I can. So it would be club soda with lime this evening, but the jalapeno cornbread muffins were perfect.

Afterwards, it was more friends at Palmer Place, catching up over what was for everyone else beer and appetizers and for me was in iced tea. Soon after, it was back to Julie’s, where some misfortune with some spare keys will remain a family legend for years to come.

Saturday morning is always scheduled as a day of “active rest.” In short, if anything goes wrong, I would be able to fix it on this day, but usually I’m just trying to find ways to drink water and kill time, and because there’s very little to distract me, I wind up being alone with my thoughts a little more than I’d like. So the morning consisted of sorting out the stuff I’d gotten at the expo the day before, asking Julie if she had any use for unusual food items (gel samples? Granola bars? Electrolyte capsules?) and preparing my stuff for the next day. It used to be I needed lots of people around to bounce ideas off of and carry things, but with this being my 17th triathlon, I can break it down to a reasonable degree of precision. It can all fit in one bag, and this stays next to my bicycle. I get a separate “shoreline” bag that has my swim cap, goggles, wetsuit, and gel pack that serves as my breakfast 15 minutes before the start. Julie or Ken can stuff this into their backpack and carry it for me until the end of the race, or, since it’s just the plastic bag from the Expo, throw it out. (It’s useful to hang onto it for hauling out the wetsuit later.)

Before it all fits into my race bag, though, it’s got to be laid out. Mentally, I stand in front of it, picturing where the items go on the bike, what I’m going to put on in what order, because seconds count. If I don’t see the item in front of me, I have to know why. I also have to make sure that some of the things that I need for this race specifically are there. When I come out of the swim, I have to run 400 yards across an asphalt path and up a small hill that usually gets muddy. Since the condition of my feet is very important for the next two hours, I keep a small plastic tub in transition with about a half gallon of water in it. Whatever grass and rocks have stuck to them in that little jaunt to my stuff get washed and dried in very short order.

Socks go in the bicycle shoes, which have their Velcro undone, and the skullcap, gloves and sunglasses are in the helmet, which is attached to the left aerobar. The socks and shoes go on after I’ve dried my feet with the sport towel, and then all the stuff on the handlebars, and out we go. I was set.

I started packing my bags. I pulled off the plastic water bottle cages on the frame of my bike; with the water bottle between my aerobars, I wouldn’t need any water down there, so I’d rather cut the whopping four ounces of weight and whatever wind drag something less than the width of a pencil would provide. I attached my new aerobar pads and hooked on the rubber bands for the water bottles, and picked up small zip ties for the numbers that attach to the bike. After that, it was just a matter of killing time and reading newspapers until showers and the Last Supper.

The “last supper” is the last meal that I eat before I race, and it’s the same thing no matter what city I’m in. I always go to an exceptionally nice seafood restaurant, because that way I know the fish will be fresh and not frozen or microwaved. (That’s one of the reasons I’ll never race in Lake Havasu City again.) The meal consists of a shrimp cocktail, swordfish, a vegetable, club soda, and water. In Chicago the meal’s always terrific, and that night was certainly no exception. We were at Parker’s Ocean Grill, with Ken and my family, and my usual menu was present.

My state of mind going into this race was better than most. I couldn’t know the course any better, I couldn’t have prepared much better than I did, and everything had gone smoothly up to this point. I made it back home by 9:30 and went to sleep.

Race morning for Chicago starts very early. The transition area opens at 4 AM, and is closed at 6. Even though I wouldn’t be starting until after 9:30, all of my stuff had to be in an assigned area in the middle of the night. I brought a headlamp and the bags of gear I’d be needing while Ken came by to make sure I didn’t flip out. In the early days, he would be carrying all kinds of extra stuff, in case I changed my mind about what was necessary to have on my right at the moment of the race. Now, most triathlons I attend alone and I’m just grateful for the company. We took some high speed pictures as we drove in on the Eisenhower.

Hundreds of people walked to their spots. I looked around as people couldn’t find the signs, the same problem I had a few years ago, and tried to figure out the best way to lay out their stuff, like I used to do, way back before I got the process as simplified as I described it above (and you know that this sport warms my OCD little heart when it takes that long to describe something simple). I got to an area that I could spot with some permanent landmarks, like a fence and a giant sign advertising Polar heart monitors, and walked my way in and out to know exactly where my stuff would be once I was disoriented getting out of the water. I filled the water bottles and the foot tub, and we were on our way back to Julie’s shortly.

Once there, I was able to nap for a couple hours, and then got my racing clothes on. I’d brought four different yellow shirts with me in a variety of styles and sizes but ultimately decided on the same one I’d worn in every race so far this year. All of my shoreline stuff was in a plastic bag. I had my usual pre-race meal of cream of rice cereal with red pepper mixed in. We drove down and set up shop on a hill about 100 feet from the swim start and took some pictures. Now all we had to do was wait, and there wasn’t anything else I could ask for. The setup for the whole day looked like it would be excellent. As long as I didn’t get into trouble in the water and didn’t hit any huge holes on the bike, I was going to be fine.

The hum sound started getting louder in my head. I put the wetsuit on over my legs. I was well aware that everything I’d trained for this year was going to be over in less than a few hours. While I wanted to make sure I had a good time, because it’s not like I get paid for doing this, I was getting to a place where I could be extremely focused. I stretched my legs and arms a little bit, and took inventory of how I was feeling; back a little sore, hips a little tight, but nothing on either count that should bother me much.

I’d already left a message with Nannette - another superstition down - and it was time to get moving. I saw where my group was, ate the last gel pack before I got in the water, looked back at Julie and Ken, smiled and said, “Showtime.” We exchanged fist-bumps and I was on my way.

In the crowd, there were people who needed assistance with their wetsuits, people who weren’t in the right place, and people who were very concerned about what was about to happen. I wasn’t nervous or shaking, but there was a level of anxious. My one objective when I was getting into the water was to stake out a spot where I could have a good swim, which I felt would be on the inside about midway through the pack.

The race announcers were shouting and recognizing people in the crowd holding signs; these are more for the spectators than the athletes in the chute. We’ll yell if people around us start yelling, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard anything said during those that I’ve remembered for more than 20 seconds. I did see, though, that when the number of people who indicated that it was their first triathlon seemed to be a third of my wave, I decided to move into the front third of the pack of swimmers. New swimmers panic; they also stop.

Triathlon swimming is closer to water polo than any actual swim training that most people do. In regular lap swimming the goal is to swim smooth across the pool in as few strokes as possible, make the most efficient use of your body’s positioning to generate power without increasing drag. The people who’ve swam in triathlons are already laughing at this sentence. You start in the water with about 200 other people at this race; few of them have any experience at all on how to swim in a crowd. You will be kicked, hit, grabbed, and slammed into as everybody tries to sort themselves out. I strode down into the water and got to my assigned space. I studied the time delta-3:40-so I’d know about where I was to get under three hours.

They began to yell out times remaining. “FIFTEEN SECONDS!”

I looked around and said the same thing I do at every race. “Good luck today, gentlemen!” Last superstition down.

I started my watch and rolled down the sleeve of my wetsuit.

The horn sounded; the churn began. I found a swimmer that was a little faster than I was and got on his feet, helping me go a little faster. Both of my sides were being pounded, but my breathing was good.

I found through the whole race that there was more contact on this swim than any I’d ever done before. Even the pictures that my sister took show me getting hit by another swimmer. I had to hip check at least three people, was hit in the temple once, struck in the left leg, but still put in a very respectable time. I had to do a lot of moving around to get clear of the maelstrom, though, and as I took off the top half of my wetsuit and made my way back to transition, I saw a lot of the swim caps around me were the colors ahead of me, so I guessed I was doing OK.

In Chicago, your time in the water is not the trickiest part of your swim, even one as concussive as that one was. There’s a 400 yard jog from the water’s exit to the transition area, and probably another 400 yards or so to your stuff, depending on where your wave is located. The path is asphalt, then onto some grass, which is a touch stomped on and muddy by the time my wave got there, and then across an asphalt path again that inexplicably had loose gravel on it.

“Wow,” I muttered. “Where’s the broken glass section?”

I made my way back to my transition area, quickly stripping off my wetsuit and getting my feet rinsed off. I glanced at my watch, which indicated I was at about the 36 minute mark. In my head, I gave myself 45 minutes on the swim, an hour and 20 on the bike, and 55 minutes on the run if I wanted to get there, so the being ahead was a nice plus, but I didn’t want to squander it by making any mistakes. I got my shoes on, had everything in place, strode out of the transition area and jumped on my bike.

At the Chicago Triathlon, cyclists ride up the Randolph Street on ramp and over the Chicago River to battle it out on Lake Shore Drive. The sheer logistical madness of this has always amazed me. Wherever you are from, you’ll probably never get to run a race on a road this large. You’ll never ride bikes on the Pacific Coast Highway, or on the Champs Elysees unless you’re willing to ride about 1200 miles for three weeks in the Tour de France. But you can ride alongside Lincoln Park and see the northern half of the skyline if you do this race.

To your left as you come out of the tunnel, you see North Pier and the riverfront. To your right, Lake Michigan, on the other side of two lanes of traffic that may contain one irate motorist who says, “Fuck these people,” and starts running over cones. I jumped into the left side of the right of the two lanes and got into tuck position by the time I was at the top of the bridge.

The first thing I noticed was, I was riding a lot faster than most of my competitors. In order to pass me they had to get on the far right side, and the only people who seemed to be doing that had much faster bicycles, much bigger legs, and conical helmets. The ratio of people that I was passing and never seeing again was quite high.

The second thing I noticed was actually a pretty serious problem. My right aerobar was a little bit shaky. In this picture from an event in October, you can see how I’m normally set up – my hands are out in front of me, away from the gear shifter/brake levers, and I’m balanced on my elbows.

Well, I’d noticed the one on the right was loose. It was my own fault – I’d moved it to accommodate the new water bottle and didn’t fully tighten it, so I could feel it shaking a little.

I started adding up in my head what could happen. First off, the only way that the aerobar could fall off is if the screws at the bottom disconnected entirely. That wasn’t going to happen; the reason this was happening was the center piece where the handlebars attached to the frame got skinnier towards the outside. When I moved them I hadn’t tightened them enough.

Do I get off the bike and fix it? No, I’m moving really well. I had the tools but that would add on five minutes – five minutes I wasn’t sure that I had to spare. The worst thing that could happen is the aerobar could give way and my right shoulder would pitch forward, and I’d fall into another rider or onto my right side. I realized, though, that if I flexed my right arm and balanced on my elbow, the only time the aerobar would drop down was when I had to shift gears. Ironically, the zip ties that held my water bottle into place would also ensure I didn’t lose the aerobar.

Knowing the relative levels of safety, I decided to go on. Traveling in the left lane, I passed dozens of people, watching very carefully for potholes, many of which were marked with spray paint. I couldn’t see my watch with the angle I was at and I decided that today was the day to make all the hill work pay off. If I shifted the gear or even hit the brake on the right side – the back brake, the one you always stop with first – I’d have to reach over the front and pick up the aerobar again.

Southbound on Lake Shore Drive after the turn, I saw a pothole so large it was filled with sand and had a traffic cone in it. I made a mental note of its location and made my way around for the seond lap. I was drinking my water quicker than usual because I didn’t want to strain the zip ties that, for all I knew, could be holding up that aerobar. I knew I’d have to pay attention to hydration a little more when I hit transition, but everything was leveled right so I wasn’t anticipating trouble.

I knew I was riding fast, and everything except for the stupid aerobar felt great. When I hit the transition area I had a very good sense of where everything was located. I got to my stuff without getting lost, which had been a problem the year before.

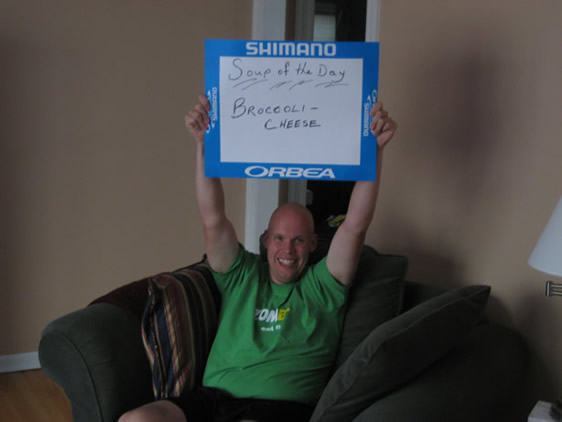

As I ran back to the timing mat I started doing an assessment of how I was feeling. My hips were a little tight, and my back was a little bit sore. I thought about it, and then I realized: hey, wait a second, that’s exactly how I felt before I started the race. I looked in the usual spot where I’d see my family. My dad was holding a sign reading “Soup of the Day: Broccoli Cheese” and Julie had one reading “You Can’t Spell “Lyden” without OCD.” Ken had the sign we’d created before we left for the race – the one that totaled up my mileage remaining for 2008, two more Olympic triathlons and the Silverman – reading “Only 139 Miles To Go.” I laughed and told them I was feeling pretty good, slugging some water. I saw that I would have to complete my run in under an hour if I wanted to break three, but I wasn’t spending a lot of time doing math.

The run course was a little different, but still retained its unique challenges. First, about 500 yards out of transition, you’re running on grass and crossing a few sidewalks until you get down to the museum, and since a few thousand other people have run that way already, there’s a dirt trail that’s burned in, and I like to stay out of that valley; I always feel like I’m going to turn an ankle. From there, it’s onto concrete, making your way down to McCormick Place.

Due to construction, the run course went past the front steps of the Field Museum, than down around to the curved seawall by the Shedd Aquarium. It continued its normal route to Adler Planetarium. My legs were feeling good, and a lot of the wave numbers on the calves around me were lower than mine, so I was ahead of a lot of competitors. The run proceeded across crosswalks, along sidewalks, in and out of the shade. I walked a total of thirty steps to catch my breath in the trip out to the turnaround.

Time-wise, I knew things were looking OK. I knew my legs would pace out well enough that all I had to do was keep running, not get outside of myself, stay on the same pace that I’d practiced so many times. I watched as Soldier Field grew closer, thanked the police officers blocking traffic at the crosswalks, reeled in a couple people who were within reach, but this part was all about pace. Once I hit the last crosswalk, knowing I had about ¾ of a mile to go, I wouldn’t allow myself any more stops. By the time I hit the aquarium again, I knew things were probably looking good. I knew, also, that I was getting a little worn out. But it was Closing Time. I had days to get over any residual soreness.

I could hear the loudspeakers announcing the finishers; I could hear an enormous crowd lining the streets. I was in a good pack of racers around me, some of them breaking into a sprint. On the last hill before the curve onto Randolph Street, I saw Ken holding up a sign:

“THE END IS NIGH”

I cracked up. My sister, I think, got a terrific picture of this moment after I saw the sign; you can see that everyone else looks like they’re going to vomit, and I’m laughing my ass off. At this point I knew where the deltas were at without looking at my watch; as soon as I turned that corner I’d be able to look at the giant digital timer, and by the minutes and seconds I’d know if I was under three hours. My guess was that I was on pace, but what if I’d hit a button wrong or something?

I turned the corner into hundreds of spectators, banners lining the streets, flags for the last 50 yards. A lot of the grimacing people in the picture had passed me, but it didn’t matter. I was going to run my race, and then I got a look at the timer.

I was under three hours by seven minutes and change.

I beamed. Then I clenched my fists and got into a cruising sprint, getting set for the finish. There’s a way to finish these races, and I always like to prove that the race didn’t beat me. I’d surpassed a goal that I’d worked at for two years. I jumped in the air, punching with my right hand, and shouted. I was waiting on the numbers, but I knew from the board. I knew from the run, I knew from the ride, I KNEW.

I staggered forward and was given a medal and a towel. Other volunteers brought me water and a banana. I staggered around for a bit, and looked at my own watch. It was reading 2:54, but I would have the official details for a minute or two.

I met Ken, Julie, and my parents at the fence. Ken handed me his cell phone:

Athlete JAMES LYDEN completed the run 2:52:51.

Wow. I was nearly 10 minutes below last year’s time, under my goal by a significant margin. I laughed and pumped my fist. I texted everyone who had been along for the ride one way or another:

WE DID IT! 2:52:51 in the Chicago Triathlon, almost 10 min better than last year. Feel great. Party time. Talk to you soon!

Messages from five states started pouring in, congratulating me. My phone wouldn’t stop ringing with people calling and talking about the messages – (“I was in church and I heard my phone beep, and I said, I can’t look, but I couldn’t resist!”) Ken and I took some pictures at Buckingham Fountain as we made our way back to load out my stuff. It took us forever to get out of the parking garage.

The night consisted of a raucous party with multiple locations, all of the tequila and then some. A whirlwind trip completed with my flight home the next day.

Three weeks later, I was standing in front of the display case at a jeweler’s in Henderson. I’d looked at this model of Tag Heuer watch in multiple stores, different states, wondering when, even wondering IF. I’d ridden a thousand miles to train for that day in August. I’d run for hours. During all of those you could pull a hamstring, blow out a tire, fall, get sick, get hurt. The day of the race you could wake up with the stomach flu. You could get kicked in the face during the swim and get knocked unconscious. You could lose a whole life’s worth of things and still never see this moment.

The saleswoman put it on my wrist and I saw my profile in the mirror. I felt the weight on my wrist, saw the gleam, and handed it back to her. I looked over at that profile in the mirror and remembered all that struggle, all that pain, all those years, and here was the trophy. I blinked back tears.

In one month, I’d get the watch engraved on the band. The date, 8/24/08. Inside, the time, 2:52:51. And, in large letters on the clasp, the word NICE in capital letters:

Nothing

Important

Comes

Easy.